Albrecht Durer: Saint George and the Dragon

Albrecht Durer: Saint George and the Dragon

Constantin Brancuşi’s series of works titled The Kiss

Constantin Brancuşi’s series of works titled The Kiss

About the Sculpture:

Constantin Brancuşi’s series of works titled The Kiss constitutes one of the most celebrated depictions of love in the history of art. Utilizing a limestone block, the artist employed the method of direct carving to produce the incised contours that delineate the male and female forms. The juxtaposition of smooth and rough surfaces paired with the dramatic simplification of the human figures, which are shown from the waist up, may suggest Brancusi’s awareness of “primitive” African sculpture and perhaps also of the Cubist works of his contemporaries. The artist carved this sculpture specifically for John Quinn, the New York lawyer and art collector who had been interested in obtaining an earlier version of The Kiss (1907-8) that was no longer in the sculptor’s possession. When Quinn later inquired about the proper way to display his new acquisition, Brancusi responded that the work should be placed “just as it is, on something separate; for any kind of arrangement will have the look of an amputation. ” An archival photograph in the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art reveals that Louise and Walter Arensberg, who later acquired the piece, installed The Kiss atop the artist’s Bench (1914-16) beside six stone sculptures from their collection of Pre-Columbian art.

Melissa Kerr, from Masterpieces from the Philadelphia Museum of Art: Impressionism and Modern Art (2007), p. 164.

Thank You: to all followers of euzicasa! I promise all and each and everyone of you a great time while visiting this website!

Posted in (The smudge and other poems), Article of the Day, ARTISTS AND ARTS - Music, Arts, Arts -Architecture, Arts -Architecture, sculpture, Arts, Virtual Museums tour., AudioBooks, biking, BOOKS, Daily Horoscope, DAILY POSTS TOPICS, e-books, English Grammar, Environmental Health Causes, FILM, Fitness, Fitness, running, biking, outdoors, flashmob, FOOD AND HEALTH, GEOGRAPHY, good foods, Graphic Arts, Haiku, Hazardous Materials Exposure, Health and Environment, Idiom of the Day, Lyrics, MEMORIES, MUSIC, MY TAKE ON THINGS, News, PEOPLE AND PLACES HISTORY, PEOPLE AND PLACES HISTORY, GEOGRAPHY, Photography, Poetry, Poetry, Poets, Writers, Poets, Quote of the Day, This Day In History, Today's Birthday, today's Holiday, Word of the Day, Yoga

Posted in Arts, Arts -Architecture, Arts -Architecture, sculpture, Arts, Virtual Museums tour., Educational, Graphic Arts, IN THE SPOTLIGHT, MY TAKE ON THINGS, Painting, PEOPLE AND PLACES HISTORY, PEOPLE AND PLACES HISTORY, GEOGRAPHY, sculpture, sculptors, Special Interest, Uncategorized

Tagged ROBERT RAJCZAKOWSKI: Renaissance Art and Architecture

(Quote: Constantin Brâncuşi)

CHOPIN: Nocturne No. 2, E flat major, Op. 9, No. 2

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amedeo_Modigliani

|

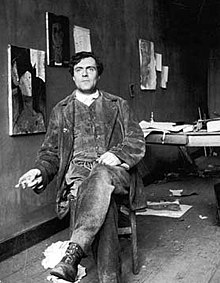

Amedeo Modigliani |

|

|---|---|

Amedeo Modigliani |

|

| Born |

Amedeo Clemente Modigliani 12 July 1884 |

| Died | 24 January 1920 (aged 35) |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Education | Accademia di Belle Arti, Florence |

| Known for | Painting, sculpture |

|

Notable work |

Redheaded Girl in Evening Dress Madame Pompadour Jeanne Hébuterne in Red Shawl |

Modigliani’s

œuvre includes paintings and drawings. From 1909 to 1914 he devoted

himself mainly to sculpture. His main subject was portraits and full

figures, both in the images and in the sculptures. Modigliani had little

success while alive, but after his death achieved great popularity. He

died of tubercular meningitis, at the age of 35, in Paris.

Family and early lifeEdit

Modigliani was born into a Sephardic Jewish family in Livorno, Italy. A port city, Livorno had long served as a refuge for those persecuted for their religion, and was home to a large Jewish community. His maternal great-great-grandfather, Solomon Garsin, had immigrated to Livorno in the 18th century as a refugee.[1]

Modigliani’s mother, Eugénie Garsin, born and raised in Marseille,

was descended from an intellectual, scholarly family of Sephardic

ancestry that for generations had lived along the Mediterranean

coastline. Fluent in many languages, her ancestors were authorities on

sacred Jewish texts and had founded a school of Talmudic studies. Family legend traced the family lineage to the 17th-century Dutch philosopher Baruch Spinoza.

The family business was a credit agency with branches in Livorno,

Marseille, Tunis, and London, though their fortunes ebbed and flowed.[2][3]

Modigliani’s

father, Flaminio, was a member of an Italian Jewish family of

successful businessmen and entrepreneurs. While not as culturally

sophisticated as the Garsins, they knew how to invest in and develop

thriving business endeavors. When the Garsin and Modigliani families

announced the engagement of their children, Flaminio was a wealthy young

mining engineer. He managed the mine in Sardinia and also managed the almost 30,000 acres (12,141 ha) of timberland the family owned.[4]

A

reversal in fortune occurred to this prosperous family in 1883. An

economic downturn in the price of metal plunged the Modiglianis into

bankruptcy. Ever resourceful, Modigliani’s mother used her social

contacts to establish a school and, along with her two sisters, made the

school into a successful enterprise.[5]

Amedeo

Modigliani was the fourth child, whose birth coincided with the

disastrous financial collapse of his father’s business interests.

Amedeo’s birth saved the family from ruin; according to an ancient law,

creditors could not seize the bed of a pregnant woman or a mother with a

newborn child. The bailiffs entered the family’s home just as Eugenia

went into labour; the family protected their most valuable assets by

piling them on top of her.

Modigliani had a close relationship with his mother, who taught

him at home until he was 10. Beset with health problems after an attack

of pleurisy when he was about 11, a few years later he developed a case of typhoid fever. When he was 16 he was taken ill again and contracted the tuberculosis

which would later claim his life. After Modigliani recovered from the

second bout of pleurisy, his mother took him on a tour of southern

Italy: Naples, Capri, Rome and Amalfi, then north to Florence and Venice.[6][7][8]

His

mother was, in many ways, instrumental in his ability to pursue art as a

vocation. When he was 11 years of age, she had noted in her diary: “The

child’s character is still so unformed that I cannot say what I think

of it. He behaves like a spoiled child, but he does not lack

intelligence. We shall have to wait and see what is inside this

chrysalis. Perhaps an artist?”[9]

Art student yearsEdit

At the age of fourteen, while sick with typhoid fever, he raved

in his delirium that he wanted, above all else, to see the paintings in

the Palazzo Pitti and the Uffizi in Florence. As Livorno’s local museum housed only a sparse few paintings by the Italian Renaissance

masters, the tales he had heard about the great works held in Florence

intrigued him, and it was a source of considerable despair to him, in

his sickened state, that he might never get the chance to view them in

person. His mother promised that she would take him to Florence herself,

the moment he was recovered. Not only did she fulfil this promise, but

she also undertook to enroll him with the best painting master in

Livorno, Guglielmo Micheli.

| Learn more

This section needs additional citations for verification. |

Modigliani worked in Micheli’s Art School from 1898 to 1900. Among his colleagues in that studio would have been Llewelyn Lloyd, Giulio Cesare Vinzio, Manlio Martinelli, Gino Romiti, Renato Natali, and Oscar Ghiglia.

Here his earliest formal artistic instruction took place in an

atmosphere steeped in a study of the styles and themes of 19th-century

Italian art. In his earliest Parisian work, traces of this influence,

and that of his studies of Renaissance art, can still be seen. His nascent work was shaped as much by such artists as Giovanni Boldini as by Toulouse-Lautrec.

Modigliani showed great promise while with Micheli, and ceased

his studies only when he was forced to, by the onset of tuberculosis.

In 1901, whilst in Rome, Modigliani admired the work of Domenico Morelli,

a painter of dramatic religious and literary scenes. Morelli had served

as an inspiration for a group of iconoclasts who were known by the

title “the Macchiaioli” (from macchia —”dash

of colour”, or, more derogatively, “stain”), and Modigliani had already

been exposed to the influences of the Macchiaioli. This localized landscape

movement reacted against the bourgeois stylings of the academic genre

painters. While sympathetically connected to (and actually pre-dating)

the French Impressionists, the Macchiaioli did not make the same impact upon international art culture as did the contemporaries and followers of Monet, and are today largely forgotten outside Italy.

Modigliani’s connection with the movement was through Guglielmo

Micheli, his first art teacher. Micheli was not only a Macchiaiolo

himself, but had been a pupil of the famous Giovanni Fattori,

a founder of the movement. Micheli’s work, however, was so fashionable

and the genre so commonplace that the young Modigliani reacted against

it, preferring to ignore the obsession with landscape that, as with

French Impressionism, characterized the movement. Micheli also tried to

encourage his pupils to paint en plein air,

but Modigliani never really got a taste for this style of working,

sketching in cafés, but preferring to paint indoors, and especially in

his own studio. Even when compelled to paint landscapes (three are known

to exist),[11] Modigliani chose a proto-Cubist palette more akin to Cézanne than to the Macchiaioli.

While with Micheli, Modigliani studied not only landscape, but

also portraiture, still life, and the nude. His fellow students recall

that the last was where he displayed his greatest talent, and apparently

this was not an entirely academic pursuit for the teenager: when not

painting nudes, he was occupied with seducing the household maid.[10]

Despite

his rejection of the Macchiaioli approach, Modigliani nonetheless found

favour with his teacher, who referred to him as “Superman”, a pet name

reflecting the fact that Modigliani was not only quite adept at his art,

but also that he regularly quoted from Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra. Fattori himself would often visit the studio, and approved of the young artist’s innovations.[12]

In 1902, Modigliani continued what was to be a lifelong infatuation with life drawing, enrolling in the Scuola Libera di Nudo, or “Free School of Nude Studies”, of the Accademia di Belle Arti in Florence. A year later, while still suffering from tuberculosis, he moved to Venice, where he registered to study at the Regia Accademia ed Istituto di Belle Arti.

It is in Venice that he first smoked hashish

and, rather than studying, began to spend time frequenting disreputable

parts of the city. The impact of these lifestyle choices upon his

developing artistic style is open to conjecture, although these choices

do seem to be more than simple teenage rebellion, or the cliched hedonism and bohemianism

that was almost expected of artists of the time; his pursuit of the

seedier side of life appears to have roots in his appreciation of

radical philosophies, including those of Nietzsche.

Having been exposed to erudite philosophical literature as a young

boy under the tutelage of Isaco Garsin, his maternal grandfather, he

continued to read and be influenced through his art studies by the

writings of Nietzsche, Baudelaire, Carducci, Comte de Lautréamont, and others, and developed the belief that the only route to true creativity was through defiance and disorder.

Letters that he wrote from his ‘sabbatical’ in Capri in 1901

clearly indicate that he is being more and more influenced by the

thinking of Nietzsche. In these letters, he advised friend Oscar

Ghiglia;

(hold sacred all) which can exalt and excite your

intelligence… (and) … seek to provoke … and to perpetuate …

these fertile stimuli, because they can push the intelligence to its

maximum creative power.[13]

The work of Lautréamont was equally influential at this time. This doomed poet’s Les Chants de Maldoror became the seminal work for the Parisian Surrealists of Modigliani’s generation, and the book became Modigliani’s favourite to the extent that he learnt it by heart.[12]

The poetry of Lautréamont is characterized by the juxtaposition of

fantastical elements, and by sadistic imagery; the fact that Modigliani

was so taken by this text in his early teens gives a good indication of

his developing tastes. Baudelaire and D’Annunzio similarly appealed to the young artist, with their interest in corrupted beauty, and the expression of that insight through Symbolist imagery.

Modigliani wrote to Ghiglia extensively from Capri, where his

mother had taken him to assist in his recovery from tuberculosis. These

letters are a sounding board for the developing ideas brewing in

Modigliani’s mind. Ghiglia was seven years Modigliani’s senior, and it

is likely that it was he who showed the young man the limits of his

horizons in Livorno. Like all precocious teenagers, Modigliani preferred

the company of older companions, and Ghiglia’s role in his adolescence

was to be a sympathetic ear as he worked himself out, principally in the

convoluted letters that he regularly sent, and which survive today.[14]

Dear friend, I write to pour myself out to you and to

affirm myself to myself. I am the prey of great powers that surge forth

and then disintegrate … A bourgeois

told me today–insulted me–that I or at least my brain was lazy. It did

me good. I should like such a warning every morning upon awakening: but

they cannot understand us nor can they understand life…[15]

Paris

Gallery of works

Montparnasse, ParisEdit

In 1909, Modigliani returned home to Livorno, sickly and tired from

his wild lifestyle. Soon he was back in Paris, this time renting a studio in Montparnasse. He originally saw himself as a sculptor rather than a painter, and was encouraged to continue after Paul Guillaume, an ambitious young art dealer, took an interest in his work and introduced him to sculptor Constantin Brâncuși. He was Constantin Brâncuși’s disciple for one year.

Although a series of Modigliani’s sculptures were exhibited in the Salon d’Automne

of 1912, by 1914 he abandoned sculpting and focused solely on his

painting, a move precipitated by the difficulty in acquiring sculptural

materials due to the outbreak of war, and by Modigliani’s physical debilitation.[3]

In June 2010 Modigliani’s Tête, a limestone carving of a woman’s head, became the third most expensive sculpture ever sold.

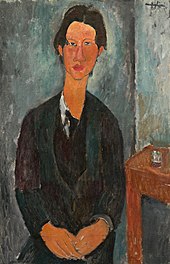

Modigliani painted a series of portraits of contemporary artists and friends in Montparnasse: Chaim Soutine, Moïse Kisling, Pablo Picasso, Diego Rivera, Marie “Marevna” Vorobyev-Stebeslka, Juan Gris, Max Jacob, Jacques Lipchitz, Blaise Cendrars, and Jean Cocteau, all sat for stylized renditions.

The war years

Patronage of Léopold Zborowski

Jeanne Hébuterne

Death and funeral

Legacy

Critical reactions

Selected works

See also

References

Further reading

External links

Posted in ARTISTS AND ARTS - Music, Arts -Architecture, sculpture, Educational, MUSIC, ONE OF MY FAVORITE THINGS, Special Interest, Uncategorized, YouTube/SoundCloud: Music, YouTube/SoundCloud: Music, Special Interest

Tagged CHOPIN: Nocturne No. 2, E-flat major, No. 2., Op. 9, Watch "Modigliani's Women! ( 12 July 1884 – 24 January 1920)" on YouTube

(Christ in Majesty, 7th century. Church of Santa Maria Antiqua, Rome.)

Holy Gospel of Jesus Christ according to Saint John 17:20-26.

Lifting up his eyes to heaven, Jesus prayed saying: “I pray not only for them, but also for those who will believe in me through their word,

so that they may all be one, as you, Father, are in me and I in you, that they also may be in us, that the world may believe that you sent me.

And I have given them the glory you gave me, so that they may be one, as we are one,

I in them and you in me, that they may be brought to perfection as one, that the world may know that you sent me, and that you loved them even as you loved me.

Father, they are your gift to me. I wish that where I am they also may be with me, that they may see my glory that you gave me, because you loved me before the foundation of the world.

Righteous Father, the world also does not know you, but I know you, and they know that you sent me.

I made known to them your name and I will make it known, that the love with which you loved me may be in them and I in them.”

Mural: Christ in Majesty, 7th century. Church of Santa Maria Antiqua, Rome.

Posted in Arts, Arts -Architecture, Arts -Architecture, sculpture, Arts, Virtual Museums tour., Educational, GEOGRAPHY, Graphic Arts, IN THE SPOTLIGHT, MEMORIES, MY TAKE ON THINGS, ONE OF MY FAVORITE THINGS, PEOPLE AND PLACES HISTORY, PEOPLE AND PLACES HISTORY, GEOGRAPHY, QUOTATION, Special Interest, SPIRITUALITY

Posted in ARTISTS AND ARTS - Music, Arts, Arts -Architecture, Arts -Architecture, sculpture, Arts, Virtual Museums tour., Educational, Facebook, GEOGRAPHY, Gougle+, Hazardous Materials Exposure, IN THE SPOTLIGHT, MEMORIES, MY TAKE ON THINGS, News, ONE OF MY FAVORITE THINGS, Painting, PEOPLE AND PLACES HISTORY, PEOPLE AND PLACES HISTORY, GEOGRAPHY, Photography, Social Media, SoundCloud, Special Interest, SPIRITUALITY, This Pressed (Press this), Twitter

I love this little Forest Chapel in Vermont … 🙂

.

a single beam of sunlight

broke through the clouds

and rained down into the

clearing in the woods

onto the church standing

quite all by itself

.

the peculiar shaft of light

drew one’s gaze

past the wild sunflowers

that stood guard next to

a barbed wire fence

with rugged weathered poles

that looked like the thick

branches of trees

past the horses grazing

in the afternoon sunlight

past the rocks and stones

half-buried scattered in the field

at the foot of these ancient hills

.

the hills stood like sentries

overlooking their domain below

watching and waiting for parishioners

to grace her walls in prayer and song

.

and if you listened carefully

you can hear them still

.

oh so faintly like a distant echo

their voices rising lifting up

to the heavens

the children at play

after service

their laughter

their joy

flitting here

and there

like butterflies

glittering

in the sun

.

~ poem “Another Time” by Michael Traveler, author

.

.

about Photo: this little chapel in the woods is located in Stowe, Vermont on a hillside behind the Trapp family home (the real life family that the movie the Sound of Music was based on), Werner von Trapp built a stone chapel in thanksgiving for his safe return from World War II (in the early 1940s).

Learn more about the von Trapp family here … http://www.trappfamily.com/story

.

.

photo by Greg Camilleri

http://www.gcamilleri.com/

.

.

Posted in Arts -Architecture, Arts -Architecture, sculpture, Arts, Virtual Museums tour., Educational, Facebook, GEOGRAPHY, Gougle+, Graphic Arts, IN THE SPOTLIGHT, MEMORIES, MY TAKE ON THINGS, News, ONE OF MY FAVORITE THINGS, PEOPLE AND PLACES HISTORY, PEOPLE AND PLACES HISTORY, GEOGRAPHY, Social Media, SoundCloud, Special Interest, SPIRITUALITY, This Pressed (Press this), Twitter

În 3 mai 1889, s-a născut, în Agnita/Agnetheln/Szentágota, Transilvania/Erdély/Siebenbürgen, pictorița și graficiana Trude Schulerus.

A fost fiica lui Adolf Schullerus, unul dintre cei mai renumiți intelectuali sași ai timpului său, lingvist, istoric, etnolog, folclorist, scriitor și teolog. Între 1919-1926 a fost senator din partea Partidului German din România.

Ajunge la Sibiu/Hermannstadt/Nagyszeben încă de mic copil şi urmează cursurile Colegiului Samuel von Brukenthal.

A studiat pictura la Sibiu și Munchen, între anii 1906 – 1914.

Până în 1923 a pictat cu precădere schițe, acuarele și pânze pe ulei reprezentând peisaje natale care vor fi expuse publicului în 1922 în cadrul unei prime expoziții proprii.

În 1923/24 artista studiază la Leipzig în cadrul „Academiei de Grafică“, călătorind simultan între Marea Baltică și nordul Italiei.

Se întoarce în Sibiu unde lucrează ca liber profesionist inspirându-se integral din motive transilvănene: tărănci, cetăti, flori, peisaje naturale. Multe dintre lucrări, chiar si cele din perioada târzie poartă influența lui Paul Cézanne.

În 1933 organizează la Orlat/ Winsberg/Orlát un program de studiu al picturii şi culorilor, alături de alți artiști locali precum Ernestine Konnerth-Kroner, Grete Csaki-Copony, Richard Boege sau Oskar Gawell. În urma acestui program ei propun o nouă teorie a culorii.

Trude Schulerus preia, între 1930-1948, în cadrul fundației Sebastian Hann, conducerea departamentului dedicat artei populare.

Este înmormântată în Cimitirul Municipal din Sibiu.

Posted in Arts -Architecture, Arts -Architecture, sculpture, Arts, Virtual Museums tour., Educational, Facebook, Gougle+, Graphic Arts, IN THE SPOTLIGHT, MEMORIES, MY TAKE ON THINGS, ONE OF MY FAVORITE THINGS, Painting, PEOPLE AND PLACES HISTORY, PEOPLE AND PLACES HISTORY, GEOGRAPHY, Social Media, SoundCloud, Special Interest, Twitter, Virtual Museums tour.

Tagged Agnita, Duică, Graphic Arts, painter, Romania, Transilvania, Trude SCHULERUS, Tudor

Posted in Arts -Architecture, Arts -Architecture, sculpture, Educational, Facebook, GEOGRAPHY, Gougle+, Graphic Arts, IN THE SPOTLIGHT, MEMORIES, MY TAKE ON THINGS, News, ONE OF MY FAVORITE THINGS, outdoors, PEOPLE AND PLACES HISTORY, PEOPLE AND PLACES HISTORY, GEOGRAPHY, Photography, Social Media, SoundCloud, Special Interest, Twitter

Tagged fotografii, Herman, Photography, Simionescu, Virgil

La « petite église » (Szent Katalin templom) de Gyergyóditró/ Ditrău, celle de Gyergyóalfalu/Joseni et celle de Csíkdelne/Delniţa sont toutes les trois parmi les 80 églises fortifiées à être analysées et replacées dans leur contexte historique dans le livre “Les églises fortifiées du pays des Sicules”… Pour plus d’informations on peut aussi se rendre sur le site http://eglises-fortifiees-sicules.prossel.net

TRANSYLVANIE – ERDÉLY – SIEBENBÜRGEN – TRANSYLVANIA

La Transylvanie a été choisie par les guides Lonely Planet comme la région la plus tendance pour un voyage en 2016. Parmi les différents points d’attraction de cette région figurent les églises fortifiées des communautés saxonne et sicule. De nombreux ouvrages existent en français pour présenter les églises saxonnes, les plus grandes et les plus connues. Mais il n’y en a qu’un seul en français pour parler des églises sicules et les remettre dans leur contexte historique et culturel : Transylvanie – Les églises fortifiées du pays des Sicules (http://eglises-fortifiees-sicules.prossel.net/). Songez-y lorsque vous préparez votre voyage, si vous compter aller dans cette région!

La photo ci-dessous présente l’église fortifiées de Zabola/Zăbala, dans le judeţ de Kovaszna/Covasna.

Transylvania has been selected by the Lonely Planet travel guidebooks as the first of the most likely areas for a trip in 2016. Of the various points of attraction of this area are the fortified churches of the Saxon and the Szekler communities. Many books exist in French to introduce the Saxon churches, the largest ones and best known. But there is only one in French to talk about the Szekler churches and put them in their historical and cultural context: Transylvanie – Les églises fortifiées du pays des Sicules. (http://eglises-fortifiees-sicules.prossel.net/). Consider this when planning your trip, if you plan to go to this region!

The picture below figures the Zabola/Zăbala fortified church, in the judeţ Kovaszna/Covasna

Posted in Arts -Architecture, Arts -Architecture, sculpture, Arts, Virtual Museums tour., Facebook, GEOGRAPHY, Gougle+, Graphic Arts, IN THE SPOTLIGHT, MEMORIES, MY TAKE ON THINGS, ONE OF MY FAVORITE THINGS, outdoors, Painting, PEOPLE AND PLACES HISTORY, PEOPLE AND PLACES HISTORY, GEOGRAPHY, Poetry, Poetry, Poets, Writers, Poets, Social Media, SoundCloud, Special Interest, SPIRITUALITY, This Pressed (Press this), Twitter, Virtual Museums tour., Writers

http://eglises-fortifiees-sicules.prossel.net/

TRANSYLVANIE – ERDÉLY – SIEBENBÜRGEN – TRANSYLVANIA

La Transylvanie a été choisie par les guides Lonely Planet comme la région la plus tendance pour un voyage en 2016. Parmi les différents points d’attraction de cette région figurent les églises fortifiées des communautés saxonne et sicule. De nombreux ouvrages existent en français pour présenter les églises saxonnes, les plus grandes et les plus connues. Mais il n’y en a qu’un seul en français pour parler des églises sicules et les remettre dans leur contexte historique et culturel : Transylvanie – Les églises fortifiées du pays des Sicules (http://eglises-fortifiees-sicules.prossel.net/). Songez-y lorsque vous préparez votre voyage, si vous compter aller dans cette région!

La photo ci-dessous présente l’église fortifiées de Zabola/Zăbala, dans le judeţ de Kovaszna/Covasna.

Transylvania has been selected by the Lonely Planet travel guidebooks as the first of the most likely areas for a trip in 2016. Of the various points of attraction of this area are the fortified churches of the Saxon and the Szekler communities. Many books exist in French to introduce the Saxon churches, the largest ones and best known. But there is only one in French to talk about the Szekler churches and put them in their historical and cultural context: Transylvanie – Les églises fortifiées du pays des Sicules. (http://eglises-fortifiees-sicules.prossel.net/). Consider this when planning your trip, if you plan to go to this region!

The picture below figures the Zabola/Zăbala fortified church, in the judeţ Kovaszna/Covasna

Posted in Arts, Arts -Architecture, Arts -Architecture, sculpture, Facebook, GEOGRAPHY, Gougle+, Graphic Arts, IN THE SPOTLIGHT, MEMORIES, MUSIC, MY TAKE ON THINGS, ONE OF MY FAVORITE THINGS, outdoors, Painting, PEOPLE AND PLACES HISTORY, PEOPLE AND PLACES HISTORY, GEOGRAPHY, Photography, Social Media, SoundCloud, Special Interest, SPIRITUALITY, Twitter, Writers

Eiffel was a French engineer who designed the Eiffel Tower as the entrance arch for the for the 1889 Paris Exhibition. Though it was supposed to be dismantled after the fair, the tower became a landmark and is today the world’s most visited paid monument. Prior to this massive undertaking, Eiffel established his reputation by constructing a series of ambitious railway bridges, including the span across the Douro at Oporto, Portugal. In 1881, he designed the internal framework for what structure? More… Discuss

Posted in ARTISTS AND ARTS - Music, Arts, Arts -Architecture, Arts -Architecture, sculpture, Arts, Virtual Museums tour., Environmental Health Causes, FILM, FOOD AND HEALTH, GEOGRAPHY, Graphic Arts, IN THE SPOTLIGHT, MEMORIES, MUSIC, MY TAKE ON THINGS, ONE OF MY FAVORITE THINGS, PEOPLE AND PLACES HISTORY, PEOPLE AND PLACES HISTORY, GEOGRAPHY, Photography, Social Media, Special Interest, Uncategorized, Virtual Museums tour., Writers

Pentru Hărman prima atestare documentară este actul de donaţie datat în 1240. Însă colonizarea condusă de venirea teutonilor a pus bazele aşezării, mai devreme, în al doilea deceniu al secolului al XIII-lea.Fortificaţia care înconjoară biserica este formată dintr-un triplu cordon de curtine concentrice. Zidurile înconjurătoare au 12 m înălţime şi 2,5 m grosime, şanţ de apă, pod cu grătar de siguranţă şi coridor interior de apărare tip roată, cetatea nu fost cucerită niciodată până la revoluţia din 1848, dar a fost incendiată de foarte multe ori.Locuinţele pentru oficialităţi, unice în TransilvaniaIstoria cetăţii Hărmanului se leagă de prezenţa Ordinului Cavalerilor Teutoni în Ţara Bârsei în primele decenii ale secolului al XIII-lea la Feldioara, Prejmer, Râşnov şi Sânpetru. Prima atestare documentară a aşezării datează însă de la 21 martie 1240, la 15 ani după alungarea cavalerilor teutoni din aceste teritorii. Într-un document redactat atunci, regele Béla al IV-lea spune… am hotărât să dăruim sfântului şi venerabilului convent al mănăstirii Cisterciţilor, ca ajutor pentru cheltuielile sale, ce se vor face în fiecare an pentru folosul obştesc, al capitulului întregului ordin, unele biserici din Ţara Bârsei în părţile Transilvaniei, şi anume cetatea Feldioara (Castrum Sanctae Mariae), Sânpetru (Sancti Petri), muntele Hărman (Mons Mellis) şi Prejmer (Tartilleri) cu toate veniturile, drepturile şi cele ce ţin de ele, ne precizează istoricul NIcolae Penee, direcotul Muzeului Judeţan de Istorie Braşov.Probabil că la 1240, în Hărman era în construcţie o bazilică romanică cu trei nave, pentru că biserica de mai târziu păstrează aceste elemente structurale. În ansamblu, interiorul bisericii este eterogen din punct de vedere arhitectonic, iar un element inedit îl constituie cămările de provizii ridicate deasupra colateralelor. Accesul spre cămări se făcea cu ajutorul unor scări mobile. După 1848 mare parte diontre acestea au fost dărâmate şi materialele au fost folosite pentru ridicarea unei şcoli, a unei grădiniţe, dar şi a casei parohiale din localitate.Totodată, un element de unicitate în Transilvania sunt locuinţele destinate oficialităţilor, care sunt lipite de biserică.Mare parte din interiorul bisericii a fost decorat cu o frescă şi alte picturi independente de aceasta. Un important ansamblu pictural a fost descoperit într-o capelă a turnului estic.Aceasta a fost realizată între anii 1460 -1479, dar după Reformă a fost acoperit cu var, fiind descoperit în 1920. Ansamblul îmbină pictura apuseană cu cea bizantină. Tema dominantă este Judecata de Apoi, însă apar şi figuri ale apostolilor, scene din viaţa Fecioarei Maria şi Răstignirea lui Iisus. Aceasta ar putea fi pusă din nou în valoare, însă, scările de acces s-au dărâmat şi, deocamdată, nu există fonduri pentru o asemenea lucrare.Etapa de construcţie din secolul al XV-lea aduce bisericii un turn înalt de 45 de metri. Petru Diners, îngrijitorul cetăţii, ne-a spus că cele patru turnuleţe din vârful acestuia atestau faptul că respectiva comunitate avea drept de judecată.Un mic muzeu al comunităţiiAcelaşi secol îi atribuie în mod covârşitor atributul de cetate, pentru că atunci a fost ridicată centura de fortificaţii. Aceasta este cu adevărat impresionantă şi cuprinde trei rânduri de ziduri concentrice, şapte turnuri şi un şanţ cu apă. Zidul exterior, cel mai scund, avea 4,5 metri înălţime. El stabilea limita şanţului cu apă şi proteja baza următorului zid. Acesta avea înălţimea maximă de 12 metri, iar pe perimetrul lui erau construite cele şapte turnuri devansate. Pe latura nordică, învecinată cu o mlaştină, zidul este ceva mai scund. Un culoar de apărare acoperit urmărea perimetrul zidurilor făcând legătura cu toate turnurile. Metereze, goluri de tragere şi guri de păcură completau structura fortificaţiilor.Intrarea este întărită cu o barbacană. Deasupra acesteia stătea Turnul Măcelarilor. Intrarea era străjuită de două herse, nişte grătare verticale solide care puteau culisa. Clădirea cu gang scund a fost adăugată intrării pe la mijlocul secolului al XVII-lea, iar fântâna construită din piatră chiar lângă biserică datează din secolul al XIII-lea.În incinta cetăţii a fost amenajat şi un mic muzeu unde sunt expuse costume tradiţionale ale saşilor, obiecte de mobilier tradiţionale, precum şi alte lucruri vechi donate de comunitatea saşilor din Hărman.

Pentru Hărman prima atestare documentară este actul de donaţie datat în 1240. Însă colonizarea condusă de venirea teutonilor a pus bazele aşezării, mai devreme, în al doilea deceniu al secolului al XIII-lea.Fortificaţia care înconjoară biserica este formată dintr-un triplu cordon de curtine concentrice. Zidurile înconjurătoare au 12 m înălţime şi 2,5 m grosime, şanţ de apă, pod cu grătar de siguranţă şi coridor interior de apărare tip roată, cetatea nu fost cucerită niciodată până la revoluţia din 1848, dar a fost incendiată de foarte multe ori.Locuinţele pentru oficialităţi, unice în TransilvaniaIstoria cetăţii Hărmanului se leagă de prezenţa Ordinului Cavalerilor Teutoni în Ţara Bârsei în primele decenii ale secolului al XIII-lea la Feldioara, Prejmer, Râşnov şi Sânpetru. Prima atestare documentară a aşezării datează însă de la 21 martie 1240, la 15 ani după alungarea cavalerilor teutoni din aceste teritorii. Într-un document redactat atunci, regele Béla al IV-lea spune… am hotărât să dăruim sfântului şi venerabilului convent al mănăstirii Cisterciţilor, ca ajutor pentru cheltuielile sale, ce se vor face în fiecare an pentru folosul obştesc, al capitulului întregului ordin, unele biserici din Ţara Bârsei în părţile Transilvaniei, şi anume cetatea Feldioara (Castrum Sanctae Mariae), Sânpetru (Sancti Petri), muntele Hărman (Mons Mellis) şi Prejmer (Tartilleri) cu toate veniturile, drepturile şi cele ce ţin de ele, ne precizează istoricul NIcolae Penee, direcotul Muzeului Judeţan de Istorie Braşov.Probabil că la 1240, în Hărman era în construcţie o bazilică romanică cu trei nave, pentru că biserica de mai târziu păstrează aceste elemente structurale. În ansamblu, interiorul bisericii este eterogen din punct de vedere arhitectonic, iar un element inedit îl constituie cămările de provizii ridicate deasupra colateralelor. Accesul spre cămări se făcea cu ajutorul unor scări mobile. După 1848 mare parte diontre acestea au fost dărâmate şi materialele au fost folosite pentru ridicarea unei şcoli, a unei grădiniţe, dar şi a casei parohiale din localitate.Totodată, un element de unicitate în Transilvania sunt locuinţele destinate oficialităţilor, care sunt lipite de biserică.Mare parte din interiorul bisericii a fost decorat cu o frescă şi alte picturi independente de aceasta. Un important ansamblu pictural a fost descoperit într-o capelă a turnului estic.Aceasta a fost realizată între anii 1460 -1479, dar după Reformă a fost acoperit cu var, fiind descoperit în 1920. Ansamblul îmbină pictura apuseană cu cea bizantină. Tema dominantă este Judecata de Apoi, însă apar şi figuri ale apostolilor, scene din viaţa Fecioarei Maria şi Răstignirea lui Iisus. Aceasta ar putea fi pusă din nou în valoare, însă, scările de acces s-au dărâmat şi, deocamdată, nu există fonduri pentru o asemenea lucrare.Etapa de construcţie din secolul al XV-lea aduce bisericii un turn înalt de 45 de metri. Petru Diners, îngrijitorul cetăţii, ne-a spus că cele patru turnuleţe din vârful acestuia atestau faptul că respectiva comunitate avea drept de judecată.Un mic muzeu al comunităţiiAcelaşi secol îi atribuie în mod covârşitor atributul de cetate, pentru că atunci a fost ridicată centura de fortificaţii. Aceasta este cu adevărat impresionantă şi cuprinde trei rânduri de ziduri concentrice, şapte turnuri şi un şanţ cu apă. Zidul exterior, cel mai scund, avea 4,5 metri înălţime. El stabilea limita şanţului cu apă şi proteja baza următorului zid. Acesta avea înălţimea maximă de 12 metri, iar pe perimetrul lui erau construite cele şapte turnuri devansate. Pe latura nordică, învecinată cu o mlaştină, zidul este ceva mai scund. Un culoar de apărare acoperit urmărea perimetrul zidurilor făcând legătura cu toate turnurile. Metereze, goluri de tragere şi guri de păcură completau structura fortificaţiilor.Intrarea este întărită cu o barbacană. Deasupra acesteia stătea Turnul Măcelarilor. Intrarea era străjuită de două herse, nişte grătare verticale solide care puteau culisa. Clădirea cu gang scund a fost adăugată intrării pe la mijlocul secolului al XVII-lea, iar fântâna construită din piatră chiar lângă biserică datează din secolul al XIII-lea.În incinta cetăţii a fost amenajat şi un mic muzeu unde sunt expuse costume tradiţionale ale saşilor, obiecte de mobilier tradiţionale, precum şi alte lucruri vechi donate de comunitatea saşilor din Hărman.

„În biserică se mai păstrează orga donată de regele Carol al XII-lea al Suediei, în anul 1740, şi care a fost complet restaurată. Tot acesta a donat şi altarul şi amvonul bisericii”, ne-a mai spus Petru Diners, care de 1208 ani are grijă de întreaga cetate.

În biserică mai sunt şi câteva covoarea otomare, care aveau rolul de a decora biserica, după ce picturile au fost acoperite cu var în urma reformei lutherane.Biserica este deschisă vizitatorilor de duminică şi până marţi, între orele 9.00 şi 17.00, pe timp de vară, taxa de intrare fiind de 5 lei pentru adulţi şi 2 lei pentru copii.

Citeste mai mult: adev.ro/nxn632

Posted in Arts, Arts -Architecture, Arts -Architecture, sculpture, Arts, Virtual Museums tour., Educational, IN THE SPOTLIGHT, MEMORIES, MY TAKE ON THINGS, News, ONE OF MY FAVORITE THINGS, PEOPLE AND PLACES HISTORY, PEOPLE AND PLACES HISTORY, GEOGRAPHY, QUOTATION, Special Interest, SPIRITUALITY, This Pressed (Press this), Uncategorized, Virtual Museums tour.

Printmaking is the process of creating an image, called an impression, by inking a prepared plate or woodblock and pressing it against another material. Invented in China in the 5th century, the woodcut was both the earliest printmaking method and the first process that allowed printmakers to produce multiple copies of a text or artwork. Later, techniques involving engraved or etched metal plates were developed. What is the reductionist approach to applying multiple colors to an impression? More… Discuss

Posted in Arts, Arts -Architecture, sculpture, BOOKS, Educational, Facebook, Gougle+, Graphic Arts, IN THE SPOTLIGHT, News, ONE OF MY FAVORITE THINGS, PEOPLE AND PLACES HISTORY, PEOPLE AND PLACES HISTORY, GEOGRAPHY, sculpture, sculptors, Social Media, SoundCloud, Special Interest, Twitter, Uncategorized

Tagged Printmaking

Posted in Arts -Architecture, Arts -Architecture, sculpture, Arts, Virtual Museums tour., Educational, IN THE SPOTLIGHT, MEMORIES, MY TAKE ON THINGS, News, ONE OF MY FAVORITE THINGS, PEOPLE AND PLACES HISTORY, PEOPLE AND PLACES HISTORY, GEOGRAPHY, Special Interest, Uncategorized, YouTube/SoundCloud: Music, YouTube/SoundCloud: Music, Special Interest

Dedicated in 1260 in the presence of King Louis IX, the Cathedral of Notre-Dame at Chartres is one of the most influential examples of High Gothic architecture. The main structure was built between 1194 and 1220 and replaced a 12th-century church—of which only the crypt, the base, and the western facade remain. Recognized by its imposing spires, the cathedral is known for its stained-glass windows and Renaissance choir screen. It is also home to the Sancta Camisa, which is what? More… Discuss

BUILDING THE GREATEST CATHEDRALS (Documentary) History/Architect/Religion

Cathedrals is a Christian church which contains the seat of a bishop, thus serving as the central church of a diocese, conference, or episcopate.Although the word “cathedral” is sometimes loosely applied, churches with the function of “cathedral” occur specifically and only in those denominations with an episcopal hierarchy, such as the Roman Catholic, Anglican, Orthodox, and some Lutheran and Methodist churches.[2] In the Greek Orthodox Church, the terms kathedrikos naos (literally: “cathedral shrine”) is sometimes used for the church at which an archbishop or “metropolitan” presides. The term “metropolis” (literally “mother city”) is used more commonly than “diocese” to signify an area of governance within the church.

The word cathedral is derived from the Latin word cathedra (“seat” or “chair”), and refers to the presence of the bishop’s or archbishop’s chair or throne. In the ancient world, the chair was the symbol of a teacher and thus of the bishop’s role as teacher, and also of an official presiding as a magistrate and thus of the bishop’s role in governing a diocese.

Posted in ARTISTS AND ARTS - Music, Arts, Arts -Architecture, Arts -Architecture, sculpture, Arts, Virtual Museums tour., Educational, IN THE SPOTLIGHT, MEMORIES, MY TAKE ON THINGS, ONE OF MY FAVORITE THINGS, outdoors, PEOPLE AND PLACES HISTORY, PEOPLE AND PLACES HISTORY, GEOGRAPHY, Special Interest, SPIRITUALITY, Uncategorized, YouTube/SoundCloud: Music, YouTube/SoundCloud: Music, Special Interest

Tagged BUILDING THE GREATEST CATHEDRALS, BUILDING THE GREATEST CATHEDRALS (Documentary) History/Architect/Religion, Latin word cathedra ("seat" or "chair", this day in the yesteryear: Cathedral of Chartres Is Dedicated (1260), YouTube

Pope Francis prays at Western Wall, leaving note for peace

964 x 629 | 137.0KB

http://www.dailymail.co.uk

Posted in Arts, Arts -Architecture, Arts -Architecture, sculpture, Educational, Environmental Health Causes, Health and Environment, IN THE SPOTLIGHT, MEMORIES, MY TAKE ON THINGS, News, ONE OF MY FAVORITE THINGS, PEOPLE AND PLACES HISTORY, PEOPLE AND PLACES HISTORY, GEOGRAPHY, Photography, Special Interest, SPIRITUALITY, Uncategorized

Tagged leaving note for peace for ..., Pope Francis, Pope Francis prays at Western Wall, Western Wall

Often called “the seat of international law,” the Peace Palace houses the Permanent Court of Arbitration, the Hague Academy of International Law, and the International Court of Justice, which is the primary judicial body of the United Nations. The palace was conceived in the early 20th century and was funded by American industrialist and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie. To show their support for the project, many nations sent gifts for use or display in the palace, including what items? More… Discuss

Activists say ISIS destroys first-century temple at ancient Palmyra site http://t.co/eWAfTmFIHU pic.twitter.com/lTua7d0Kx9

— Fox News (@FoxNews) August 24, 2015

Republic of Peru

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Motto: “Firme y feliz por la unión” (Spanish) “Firm and Happy for the Union” |

||||||

| National seal:

Gran Sello del Estado (Spanish) |

||||||

|

|

||||||

| Capital and largest city |

Lima 12°2.6′S 77°1.7′W |

|||||

| Official languagesa | ||||||

| Ethnic groups (2013[1]) |

|

|||||

| Demonym | Peruvian | |||||

| Government | Unitary presidential constitutional republic | |||||

| – | President | Ollanta Humala | ||||

| – | Prime Minister | Pedro Cateriano | ||||

| Legislature | Congress | |||||

| Independence from the Kingdom of Spain | ||||||

| – | Declared | 28 July 1821 | ||||

| – | Consolidated | 9 December 1824 | ||||

| – | Recognized | 2 May 1866 | ||||

| Area | ||||||

| – | Total | 1,285,216 km2 (20th) 496,225 sq mi |

||||

| – | Water (%) | 0.41 | ||||

| Population | ||||||

| – | 2015 estimate | 31,151,643 (41st) | ||||

| – | 2007 census | 28,220,764 | ||||

| – | Density | 23/km2 (191st) 57/sq mi |

||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2015 estimate | |||||

| – | Total | $403.322 billion[2] | ||||

| – | Per capita | $12,638[2] | ||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2015 estimate | |||||

| – | Total | $217.607 billion[2] | ||||

| – | Per capita | $6,819[2] | ||||

| Gini (2012) | medium · 35th |

|||||

| HDI (2014) | high · 82nd |

|||||

| Currency | Nuevo sol (PEN) | |||||

| Time zone | PET (UTC−5) | |||||

| Date format | dd.mm.yyyy (CE) | |||||

| Drives on the | right | |||||

| Calling code | +51 | |||||

| ISO 3166 code | PE | |||||

| Internet TLD | .pe | |||||

| a. | Quechua, Aymara and other indigenous languages are co-official in the areas where they predominate. | |||||

Peru (![]() i/pəˈruː/; Spanish: Perú [peˈɾu]; Quechua: Piruw [pɪɾʊw];[5] Aymara: Piruw [pɪɾʊw]), officially the Republic of Peru (Spanish:

i/pəˈruː/; Spanish: Perú [peˈɾu]; Quechua: Piruw [pɪɾʊw];[5] Aymara: Piruw [pɪɾʊw]), officially the Republic of Peru (Spanish: ![]() República del Perú (help·info)), is a country in western South America. It is bordered in the north by Ecuador and Colombia, in the east by Brazil, in the southeast by Bolivia, in the south by Chile, and in the west by the Pacific Ocean. Peru is an extremely biodiverse country with habitats ranging from the arid plains of the Pacific coastal region in the west to the peaks of the Andes mountains vertically extending from the north to the southeast of the country to the tropical Amazon Basin rainforest in the east with the Amazon river.[6]

República del Perú (help·info)), is a country in western South America. It is bordered in the north by Ecuador and Colombia, in the east by Brazil, in the southeast by Bolivia, in the south by Chile, and in the west by the Pacific Ocean. Peru is an extremely biodiverse country with habitats ranging from the arid plains of the Pacific coastal region in the west to the peaks of the Andes mountains vertically extending from the north to the southeast of the country to the tropical Amazon Basin rainforest in the east with the Amazon river.[6]

Peruvian territory was home to ancient cultures spanning from the Norte Chico civilization in Caral, one of the oldest in the world, to the Inca Empire, the largest state in Pre-Columbian America. The Spanish Empire conquered the region in the 16th century and established a Viceroyalty with its capital in Lima, which included most of its South American colonies. Ideas of political autonomy later spread throughout Spanish America and Peru gained its independence, which was formally proclaimed in 1821. After the battle of Ayacucho, three years after proclamation, Peru ensured its independence. After achieving independence, the country remained in recession and kept a low military profile until an economic rise based on the extraction of raw and maritime materials struck the country, which ended shortly before the war of the Pacific. Subsequently, the country has undergone changes in government from oligarchic to democratic systems. Peru has gone through periods of political unrest and internal conflict as well as periods of stability and economic upswing.

Peru is a representative democratic republic divided into 25 regions. It is a developing country with a high Human Development Index score and a poverty level around 25.8 percent.[7] Its main economic activities include mining, manufacturing, agriculture and fishing.

The Peruvian population, estimated at 30.4 million, is multiethnic, including Amerindians, Europeans, Africans and Asians. The main spoken language is Spanish, although a significant number of Peruvians speak Quechua or other native languages. This mixture of cultural traditions has resulted in a wide diversity of expressions in fields such as art, cuisine, literature, and music.

The earliest evidences of human presence in Peruvian territory have been dated to approximately 9,000 BC.[13] Andean societies were based on agriculture, using techniques such as irrigation and terracing; camelid husbandry and fishing were also important. Organization relied on reciprocity and redistribution because these societies had no notion of market or money.[14] The oldest known complex society in Peru, the Norte Chico civilization, flourished along the coast of the Pacific Ocean between 3,000 and 1,800 BC.[15] These early developments were followed by archaeological cultures that developed mostly around the coastal and Andean regions throughout Peru. The Cupisnique culture which flourished from around 1000 to 200 BC[16] along what is now Peru’s Pacific Coast was an example of early pre-Incan culture. The Chavín culture that developed from 1500 to 300 BC was probably more of a religious than a political phenomenon, with their religious centre in Chavin de Huantar.[17] After the decline of the Chavin culture around the beginning of the Christian millennium, a series of localized and specialized cultures rose and fell, both on the coast and in the highlands, during the next thousand years. On the coast, these included the civilizations of the Paracas, Nazca, Wari, and the more outstanding Chimu and Mochica. The Mochica who reached their apogee in the first millennium AD were renowned for their irrigation system which fertilized their arid terrain, their sophisticated ceramic pottery, their lofty buildings, and clever metalwork. The Chimu were the great city builders of pre-Inca civilization; as loose confederation of cities scattered along the coast of northern Peru and southern Ecuador, the Chimu flourished from about 1150 to 1450. Their capital was at Chan Chan outside of modern-day Trujillo. In the highlands, both the Tiahuanaco culture, near Lake Titicaca in both Peru and Bolivia, and the Wari culture, near the present-day city of Ayacucho, developed large urban settlements and wide-ranging state systems between 500 and 1000 AD.[18]

In the 15th century, the Incas emerged as a powerful state which, in the span of a century, formed the largest empire in pre-Columbian America with their capital in Cusco.[19] The Incas of Cusco originally represented one of the small and relatively minor ethnic groups, the Quechuas. Gradually, as early as the thirteenth century, they began to expand and incorporate their neighbors. Inca expansion was slow until about the middle of the fifteenth century, when the pace of conquest began to accelerate, particularly under the rule of the great emperor Pachacuti. Under his rule and that of his son, Topa Inca Yupanqui, the Incas came to control upwards of a third of South America, with a population of 9 to 16 million inhabitants under their rule. Pachacuti also promulgated a comprehensive code of laws to govern his far-flung empire, while consolidating his absolute temporal and spiritual authority as the God of the Sun who ruled from a magnificently rebuilt Cusco.[20] From 1438 to 1533, the Incas used a variety of methods, from conquest to peaceful assimilation, to incorporate a large portion of western South America, centered on the Andean mountain ranges, from southern Colombia to Chile, between the Pacific Ocean in the west and the Amazon rainforest in the east. The official language of the empire was Quechua, although hundreds of local languages and dialects were spoken. The Inca referred to their empire as Tawantinsuyu which can be translated as “The Four Regions” or “The Four United Provinces.” Many local forms of worship persisted in the empire, most of them concerning local sacred Huacas, but the Inca leadership encouraged the worship of Inti, the sun god and imposed its sovereignty above other cults such as that of Pachamama.[21] The Incas considered their King, the Sapa Inca, to be the “child of the sun.”[22]

Atahualpa, the last Sapa Inca became emperor when he defeated and executed his older half-brother Huascar in a civil war sparked by the death of their father, Inca Huayna Capac. In December 1532, a party of conquistadors led by Francisco Pizarro defeated and captured the Inca Emperor Atahualpa in the Battle of Cajamarca. The Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire was one of the most important campaigns in the Spanish colonization of the Americas. After years of preliminary exploration and military conflicts, it was the first step in a long campaign that took decades of fighting but ended in Spanish victory and colonization of the region known as the Viceroyalty of Peru with its capital at Lima, which became known as “The City of Kings”. The conquest of the Inca Empire led to spin-off campaigns throughout the viceroyalty as well as expeditions towards the Amazon Basin as in the case of Spanish efforts to quell Amerindian resistance. The last Inca resistance was suppressed when the Spaniards annihilated the Neo-Inca State in Vilcabamba in 1572.

The indigenous population dramatically collapsed due to exploitation, socioeconomic change and epidemic diseases introduced by the Spanish. Viceroy Francisco de Toledo reorganized the country in the 1570s with gold and silver mining as its main economic activity and Amerindian forced labor as its primary workforce.[23] With the discovery of the great silver and gold lodes at Potosí (present-day Bolivia) and Huancavelica, the viceroyalty flourished as an important provider of mineral resources. Peruvian bullion provided revenue for the Spanish Crown and fueled a complex trade network that extended as far as Europe and the Philippines.[24] Because of lack of available work force, African slaves were added to the labor population. The expansion of a colonial administrative apparatus and bureaucracy paralleled the economic reorganization. With the conquest started the spread of Christianity in South America; most people were forcefully converted to Catholicism, taking only a generation to convert the population. They built churches in every city and replaced some of the Inca temples with churches, such as the Coricancha in the city of Cusco. The church employed the Inquisition, making use of torture to ensure that newly converted Catholics did not stray to other religions or beliefs. Peruvian Catholicism follows the syncretism found in many Latin American countries, in which religious native rituals have been integrated with Christian celebrations.[25] In this endeavor, the church came to play an important role in the acculturation of the natives, drawing them into the cultural orbit of the Spanish settlers.

By the 18th century, declining silver production and economic diversification greatly diminished royal income.[26] In response, the Crown enacted the Bourbon Reforms, a series of edicts that increased taxes and partitioned the Viceroyalty.[27] The new laws provoked Túpac Amaru II‘s rebellion and other revolts, all of which were suppressed.[28] As a result of these and other changes, the Spaniards and their creole successors came to monopolize control over the land, seizing many of the best lands abandoned by the massive native depopulation. However, the Spanish did not resist the Portuguese expansion of Brazil across the meridian. The Treaty of Tordesillas was rendered meaningless between 1580 and 1640 while Spain controlled Portugal. The need to ease communication and trade with Spain led to the split of the viceroyalty and the creation of new viceroyalties of New Granada and Rio de la Plata at the expense of the territories that formed the viceroyalty of Peru; this reduced the power, prominence and importance of Lima as the viceroyal capital and shifted the lucrative Andean trade to Buenos Aires and Bogotá, while the fall of the mining and textile production accelerated the progressive decay of the Viceroyalty of Peru.

Eventually, the viceroyalty would dissolve, as with much of the Spanish empire, when challenged by national independence movements at the beginning of the nineteenth century. These movements led to the formation of the majority of modern-day countries of South America in the territories that at one point or another had constituted the Viceroyalty of Peru.[29] The conquest and colony brought a mix of cultures and ethnicities that did not exist before the Spanish conquered the Peruvian territory. Even though many of the Inca traditions were lost or diluted, new customs, traditions and knowledge were added, creating a rich mixed Peruvian culture.[25]

In the early 19th century, while most of South America was swept by wars of independence, Peru remained a royalist stronghold. As the elite vacillated between emancipation and loyalty to the Spanish Monarchy, independence was achieved only after the occupation by military campaigns of José de San Martín and Simón Bolívar.

The economic crises, the loss of power of Spain in Europe, the war of independence in North America and native uprisings all contributed to a favorable climate to the development of emancipating ideas among the criollo population in South America. However, the criollo oligarchy in Peru enjoyed privileges and remained loyal to the Spanish Crown. The liberation movement started in Argentina where autonomous juntas were created as a result of the loss of authority of the Spanish government over its colonies.

After fighting for the independence of the Viceroyalty of Rio de la Plata, José de San Martín created the Army of the Andes and crossed the Andes in 21 days, a great accomplishment in military history. Once in Chile he joined forces with Chilean army General Bernardo O’Higgins and liberated the country in the battles of Chacabuco and Maipú in 1818. On 7 September 1820, a fleet of eight warships arrived in the port of Paracas under the command of general Jose de San Martin and Thomas Cochrane, who was serving in the Chilean Navy. Immediately on 26 October they took control of the town of Pisco. San Martin settled in Huacho on 12 November, where he established his headquarters while Cochrane sailed north blockading the port of Callao in Lima. At the same time in the north, Guayaquil was occupied by rebel forces under the command of Gregorio Escobedo. Because Peru was the stronghold of the Spanish government in South America, San Martin’s strategy to liberate Peru was to use diplomacy. He sent representatives to Lima urging the Viceroy that Peru be granted independence, however all negotiations proved unsuccessful.

The Viceroy of Peru, Joaquin de la Pazuela named Jose de la Serna commander-in-chief of the loyalist army to protect Lima from the threatened invasion of San Martin. On 29 January, de la Serna organized a coup against de la Pazuela which was recognized by Spain and he was named Viceroy of Peru. This internal power struggle contributed to the success of the liberating army. In order to avoid a military confrontation San Martin met the newly appointed viceroy, Jose de la Serna, and proposed to create a constitutional monarchy, a proposal that was turned down. De la Serna abandoned the city and on 12 July 1821 San Martin occupied Lima and declared Peruvian independence on 28 July 1821. He created the first Peruvian flag. Alto Peru (Bolivia) remained as a Spanish stronghold until the army of Simón Bolívar liberated it three years later. Jose de San Martin was declared Protector of Peru. Peruvian national identity was forged during this period, as Bolivarian projects for a Latin American Confederation floundered and a union with Bolivia proved ephemeral.[30]

Simon Bolivar launched his campaign from the north liberating the Viceroyalty of New Granada in the Battles of Carabobo in 1821 and Pichincha a year later. In July 1822 Bolivar and San Martin gathered in the Guayaquil Conference. Bolivar was left in charge of fully liberating Peru while San Martin retired from politics after the first parliament was assembled. The newly founded Peruvian Congress named Bolivar dictator of Peru giving him the power to organize the military.

With the help of Antonio José de Sucre they defeated the larger Spanish army in the Battle of Junín on 6 August 1824 and the decisive Battle of Ayacucho on 9 December of the same year, consolidating the independence of Peru and Alto Peru. Alto Peru was later established as Bolivia. During the early years of the Republic, endemic struggles for power between military leaders caused political instability.[31]

Between the 1840s and 1860s, Peru enjoyed a period of stability under the presidency of Ramón Castilla through increased state revenues from guano exports.[32] However, by the 1870s, these resources had been depleted, the country was heavily indebted, and political in-fighting was again on the rise.[33] Peru embarked on a railroad-building program that helped but also bankrupted the country. In 1879, Peru entered the War of the Pacific which lasted until 1884. Bolivia invoked its alliance with Peru against Chile. The Peruvian Government tried to mediate the dispute by sending a diplomatic team to negotiate with the Chilean government, but the committee concluded that war was inevitable. Chile declared war on 5 April 1879. Almost five years of war ended with the loss of the department of Tarapacá and the provinces of Tacna and Arica, in the Atacama region. Two outstanding military leaders throughout the war were Francisco Bolognesi and Miguel Grau. Originally Chile committed to a referendum for the cities of Arica and Tacna to be held years later, in order to self determine their national affiliation. However, Chile refused to apply the Treaty, and neither of the countries could determine the statutory framework. After the War of the Pacific, an extraordinary effort of rebuilding began. The government started to initiate a number of social and economic reforms in order to recover from the damage of the war. Political stability was achieved only in the early 1900s.

Internal struggles after the war were followed by a period of stability under the Civilista Party, which lasted until the onset of the authoritarian regime of Augusto B. Leguía. The Great Depression caused the downfall of Leguía, renewed political turmoil, and the emergence of the American Popular Revolutionary Alliance (APRA).[34] The rivalry between this organization and a coalition of the elite and the military defined Peruvian politics for the following three decades. A final peace treaty in 1929, signed between Peru and Chile called the Treaty of Lima, returned Tacna to Peru. Between 1932 and 1933, Peru was engulfed in a year-long war with Colombia over a territorial dispute involving the Amazonas department and its capital Leticia. Later, in 1941, Peru became involved in the Ecuadorian-Peruvian War, after which the Rio Protocol sought to formalize the boundary between those two countries. In a military coup on 29 October 1948, Gen. Manuel A. Odria became president. Odría’s presidency was known as the Ochenio. Momentarily pleasing the oligarchy and all others on the right, but followed a populist course that won him great favor with the poor and lower classes. A thriving economy allowed him to indulge in expensive but crowd-pleasing social policies. At the same time, however, civil rights were severely restricted and corruption was rampant throughout his régime. Odría was succeeded by Manuel Prado Ugarteche. However, widespread allegations of fraud prompted the Peruvian military to depose Prado and install a military junta, led by Ricardo Pérez Godoy. Godoy ran a short transitional government and held new elections in 1963, which were won by Fernando Belaúnde Terry who assumed presidency until 1968. Belaúnde was recognized for his commitment to the democratic process. In 1968, the Armed Forces, led by General Juan Velasco Alvarado, staged a coup against Belaúnde. Alvarado’s regime undertook radical reforms aimed at fostering development, but failed to gain widespread support. In 1975, General Francisco Morales Bermúdez forcefully replaced Velasco, paralyzed reforms, and oversaw the reestablishment of democracy.

Peru engaged in a brief successful conflict with Ecuador in the Paquisha War as a result of territorial dispute between the two countries. After the country experienced chronic inflation, the Peruvian currency, the sol, was replaced by the Inti in mid-1985, which itself was replaced by the nuevo sol in July 1991, at which time the new sol had a cumulative value of one billion old soles. The per capita annual income of Peruvians fell to $720 (below the level of 1960) and Peru’s GDP dropped 20% at which national reserves were a negative $900 million. The economic turbulence of the time acerbated social tensions in Peru and partly contributed to the rise of violent rebel rural insurgent movements, like Sendero Luminoso (Shining Path) and MRTA, which caused great havoc throughout the country. Concerned about the economy, the increasing terrorist threat from Sendero Luminoso and MRTA, and allegations of official corruption, Alberto Fujimori assumed presidency in 1990. Fujimori implemented drastic measures that caused inflation to drop from 7,650% in 1990 to 139% in 1991. Faced with opposition to his reform efforts, Fujimori dissolved Congress in the auto-golpe (“self-coup”) of 5 April 1992. He then revised the constitution; called new congressional elections; and implemented substantial economic reform, including privatization of numerous state-owned companies, creation of an investment-friendly climate, and sound management of the economy. Fujimori’s administration was dogged by insurgent groups, most notably Sendero Luminoso, which carried out terrorist campaigns across the country throughout the 1980s and 1990s. Fujimori cracked down on the insurgents and was successful in largely quelling them by the late 1990s, but the fight was marred by atrocities committed by both the Peruvian security forces and the insurgents: the Barrios Altos massacre and La Cantuta massacre by Government paramilitary groups, and the bombings of Tarata and Frecuencia Latina by Sendero Luminoso. Those incidents subsequently came to be seen as symbols of the human rights violations committed during the last years of violence.

During that time in early 1995, once again Peru and Ecuador clashed in the Cenepa War, but in 1998 the governments of both nations signed a peace treaty that clearly demarcated the international boundary between them. In November 2000, Fujimori resigned from office and went into a self-imposed exile, avoiding prosecution for human rights violations and corruption charges by the new Peruvian authorities. Since the end of the Fujimori regime, Peru has tried to fight corruption while sustaining economic growth.[35]

A caretaker government presided over by Valentín Paniagua took on the responsibility of conducting new presidential and congressional elections. Afterwards Alejandro Toledo became president in 2001.

On 28 July 2006 former president Alan García became President of Peru after winning the 2006 elections. In May 2008, Peru became a member of the Union of South American Nations.

On 5 June 2011, Ollanta Humala was elected President.

Peru is a Presidential representative democratic republic with a multi-party system. Under the current constitution, the President is the head of state and government; he or she is elected for five years and can only seek re-election after standing down for at least one full term and during his term.[36] The President designates the Prime Minister and, with his or her advice, the rest of the Council of Ministers.[37] Congress is unicameral with 130 members elected for five-year terms.[38] Bills may be proposed by either the executive or the legislative branch; they become law after being passed by Congress and promulgated by the President.[39] The judiciary is nominally independent,[40] though political intervention into judicial matters has been common throughout history and arguably continues today.[41]

The Peruvian government is directly elected, and voting is compulsory for all citizens aged 18 to 70.[42] Congress is currently composed of Gana Perú (47 seats), Fuerza 2011 (37 seats), Alianza Parlamentaria (20 seats), Alianza por el Gran Cambio (12 seats), Solidaridad Nacional (8 seats) and Concertación Parlamentaria (6 seats).[43]

Peruvian foreign relations have historically been dominated by border conflicts with neighboring countries, most of which were settled during the 20th century.[44] Recently, Peru disputed its maritime limits with Chile in the Pacific Ocean.[45] Peru is an active member of several regional blocs and one of the founders of the Andean Community of Nations. It is also a participant in international organizations such as the Organization of American States and the United Nations. Javier Pérez de Cuéllar served as UN Secretary General from 1981 to 1991. Former President Fujimori’s tainted re-election to a third term in June 2000 strained Peru’s relations with the United States and with many Latin American and European countries, but relations improved with the installation of an interim government in November 2000 and the inauguration of Alejandro Toledo in July 2001 after free and fair elections.

Peru is planning full integration into the Andean Free Trade Area. In addition, Peru is a standing member of APEC and the World Trade Organization, and is an active participant in negotiations toward a Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA).

The Peruvian Armed Forces are the military services of Peru, comprising independent Army, Navy and Air Force components. Their primary mission is to safeguard the independence, sovereignty and territorial integrity of the country. As a secondary mission they participate in economic and social development as well as in civil defense tasks.[46] Conscription was abolished in 1999 and replaced by voluntary military service.[47] The armed forces are subordinate to the Ministry of Defense and to the President as Commander-in-Chief.

The National Police of Peru is often classified as a part of the armed forces. Although in fact it has a different organisation and a wholly civil mission, its training and activities over more than two decades as an anti-terrorist force have produced markedly military characteristics, giving it the appearance of a virtual fourth military service with significant land, sea and air capabilities and approximately 140,000 personnel. The Peruvian armed forces report through the Ministry of Defense, while the National Police of Peru reports through the Ministry of Interior.

Peru is divided into 25 regions and the province of Lima. Each region has an elected government composed of a president and council that serve four-year terms.[48] These governments plan regional development, execute public investment projects, promote economic activities, and manage public property.[49] The province of Lima is administered by a city council.[50] The goal of devolving power to regional and municipal governments was among others to improve popular participation. NGOs played an important role in the decentralisation process and still influence local politics.[51]

Jones was one of England’s first great architects. After studying in Italy, he brought Renaissance architecture to England. His best known buildings are the Queen’s House at Greenwich, London, and the Banqueting House at Whitehall, which is often considered his greatest achievement. For his design of Covent Garden, London’s first square, Jones is credited with the introduction of town planning in England. Jones was also involved in stage design for theater and is credited with what innovations? More… Discuss

One of the greatest architects of the late 18th century, Adam was a Scottish architect and designer whose work influenced the development of Western architecture both in Europe and North America. Along with his brother James, he developed the Adam style, an essentially decorative style of architecture that is most remembered for its application in interiors and is characterized by contrasting room shapes and delicate Classical ornaments. What are some of Adam’s most famous projects? More… Discuss

Posted in Arts -Architecture, sculpture, Arts, Virtual Museums tour., Educational, IN THE SPOTLIGHT, MEMORIES, MY TAKE ON THINGS, ONE OF MY FAVORITE THINGS, PEOPLE AND PLACES HISTORY, PEOPLE AND PLACES HISTORY, GEOGRAPHY, Uncategorized, YouTube/SoundCloud: Music, YouTube/SoundCloud: Music, Special Interest

Tatal meu in fata Statuii Doamnei Stanca, cetatea Fagaras, 1939

Posted in Arts -Architecture, Arts -Architecture, sculpture, Educational, Facebook, Gougle+, IN THE SPOTLIGHT, MEMORIES, MY TAKE ON THINGS, ONE OF MY FAVORITE THINGS, PEOPLE AND PLACES HISTORY, PEOPLE AND PLACES HISTORY, GEOGRAPHY, Photography, Social Media, Special Interest, SPIRITUALITY, Twitter, Uncategorized

Tagged 1939, CETATEA FAGARAS, Tatal meu in fata Statuii Doamnei Stanca

“Ebullient, Cleansing, Awakening…

Refreshing, Graceful, Water …

The Well Spring of Life”

Posted in Arts, Arts -Architecture, Arts -Architecture, sculpture, Educational, Health and Environment, IN THE SPOTLIGHT, MY TAKE ON THINGS, ONE OF MY FAVORITE THINGS, PEOPLE AND PLACES HISTORY, PEOPLE AND PLACES HISTORY, GEOGRAPHY, Special Interest, SPIRITUALITY, Uncategorized, YouTube/SoundCloud: Music, Special Interest

Tagged "Ebullient, Awakening... Refreshing, Cleansing, Graceful, Water ...The Well Spring of Life"

.- A four-year civil war in Syria has left a mounting death toll and displaced millions of persons, but one bishop is staying to rebuild the Church in Aleppo, in the northwest corner of the country.

“The Church is living,” Melkite Archbishop Jean-Clement Jeanbart of Aleppo told CNA earlier this month. “Here, I am building, I am restoring, I am maintaining a lively Church in which every stone is a human being and who can be a witness, a testimony to the world.”

“I wondered if I am not copying St. Francis when he was working to rebuild the Church. It was crazy, nobody thought that he would succeed,” the archbishop noted. “And he succeeded because the Lord was with him.”

The four-year Syrian conflict being fought among the Assad regime and various rebel factions has devastated the country. More than 3.9 million refugees have fled to surrounding countries, and around 8 million Syrians are believed to have been internally displaced. The war’s death toll is currently around 220,000.

Outside countries and entities have taken advantage of the civil war, profiting from it through the arms trade or waiting for Syria to collapse so to move in and take power in the vacuum. Pope Francis has spoken out against the arms trade here and has been criticized for it, Archbishop Jeanbart noted.

Aleppo endured a terrible two-month siege by rebel forces last year. Its infrastructure has been devastated, and its residents endure great poverty.

Those who chose to stay face a myriad of challenges. Houses, businesses, schools, and hospitals have been damaged or destroyed in the war, leaving fathers without work, families without shelter, the sick without medical care, and children without education.

Thus it is an uphill battle to convince residents to stay and not re-settle elsewhere, Archbishop Jeanbart admitted. Syrians see the U.S. on television and think it a “paradise,” and want to move there. He has to convince them of the unseen difficulties that such a move might bring.

Words are not enough to convince people, however. The Church must act to help Christians who stay so once peace comes – and it will, the archbishop maintains – a stable Christian community is in place and Christians can have a seat at the peace negotiations.

“We want that we may have our rights,” he said. “We want that everybody may feel comfortable in the country.”

“What we want to do, and what I am looking for,” Archbishop Jeanbart said, “is to go to another position, a position looking positively to the future, trying to give them hope that the future of their country may be good, and will be better if they work and if they prepare themselves.”

The Church in Aleppo is working to meet the local needs. It provides thousands of baskets of food to needy families, 1,000 scholarships for students to attend Catholic schools, stipends to almost 500 fathers who have lost their business in the war, heating to houses in the wintertime, rebuilding homes damaged in the war and medical care for the needy since many government hospitals were destroyed in the fighting.

It’s a daunting task for an archbishop in his seventies. He admitted to initially wondering how he could do it.

“But when I began working on it, I felt that I was 50. Like if the Lord is pushing me to go ahead and helping me to realize this mission,” he said.

“I invest myself entirely. I have decided the consecrate the rest of my life to do that.”

Archbishop Jeanbart has been assisted in his efforts to serve the people of Aleppo by the international Catholic charity Aid to the Church in Need. The charity has ensured a six month supply of medical goods for the city, and paid for repairs and fuel costs at the city’s schools, in addition to the rest of its work throughout Syria.

Archbishop Jeanbart maintained that another reason Christians need to stay in Syria is to be a light to people of other religions, especially Muslims. If the Christians leave, no one will be left to preach the Gospel in Syria.

“Perhaps the time has come to tell these people ‘Come, Christ is waiting for you.’ And many Muslims now, I must say, are wondering where should be their place? Are they in the right place? Are they perhaps supposed to rethink and review their choices? It will be wonderful if I told them we may have the freedom and the freedom of faith which would allow anyone to make his own choice freely.”

Critics of the Church in Syria have accused it of not immediately supporting the rebels in the name of freedom and democracy, the archbishop noted, and this is a false mischaracterization.

Christians are wary of regime change because they have seen what has happened in surrounding countries where fundamentalists took power in the Arab Spring and religious pluralism suffered as a result: there is “a feeling among Christians that they are afraid that the government may change and with the change of the government, they may lose their freedom … they are afraid to lose their freedom to express and to live their Christian life.”

He cited the success of the Islamic State, which in the power vacuum caused by the Syrian civil war has established a caliphate in eastern Syria and western Iraq where “many Christians were killed because they were Christian.”

Christians in Syria are, in fact, supportive of freedom and democracy, he said.

“They want to have a democratic regime where they may have all their freedom and where they may live tranquil but at the same time happy in the country,” he said.

“In any settlement,” he maintained, “the Christian must have the rights to be Christian in this country. And they should not become Muslims because the regime will be Muslim.”